Every day across the United States, thousands of Catholic women religious show quiet heroism as they serve in education, health care and a range of social service and other ministries, including helping the poor, immigrants and women and children in need.

A Mass and rededication ceremony on Sept. 21, 2024 marking the 100th anniversary of the Nuns of the Battlefield Monument in Washington, D.C., commemorated the faith and heroism of an estimated 1,000 Catholic women religious who served as nurses during the Civil War, caring for wounded and dying soldiers.

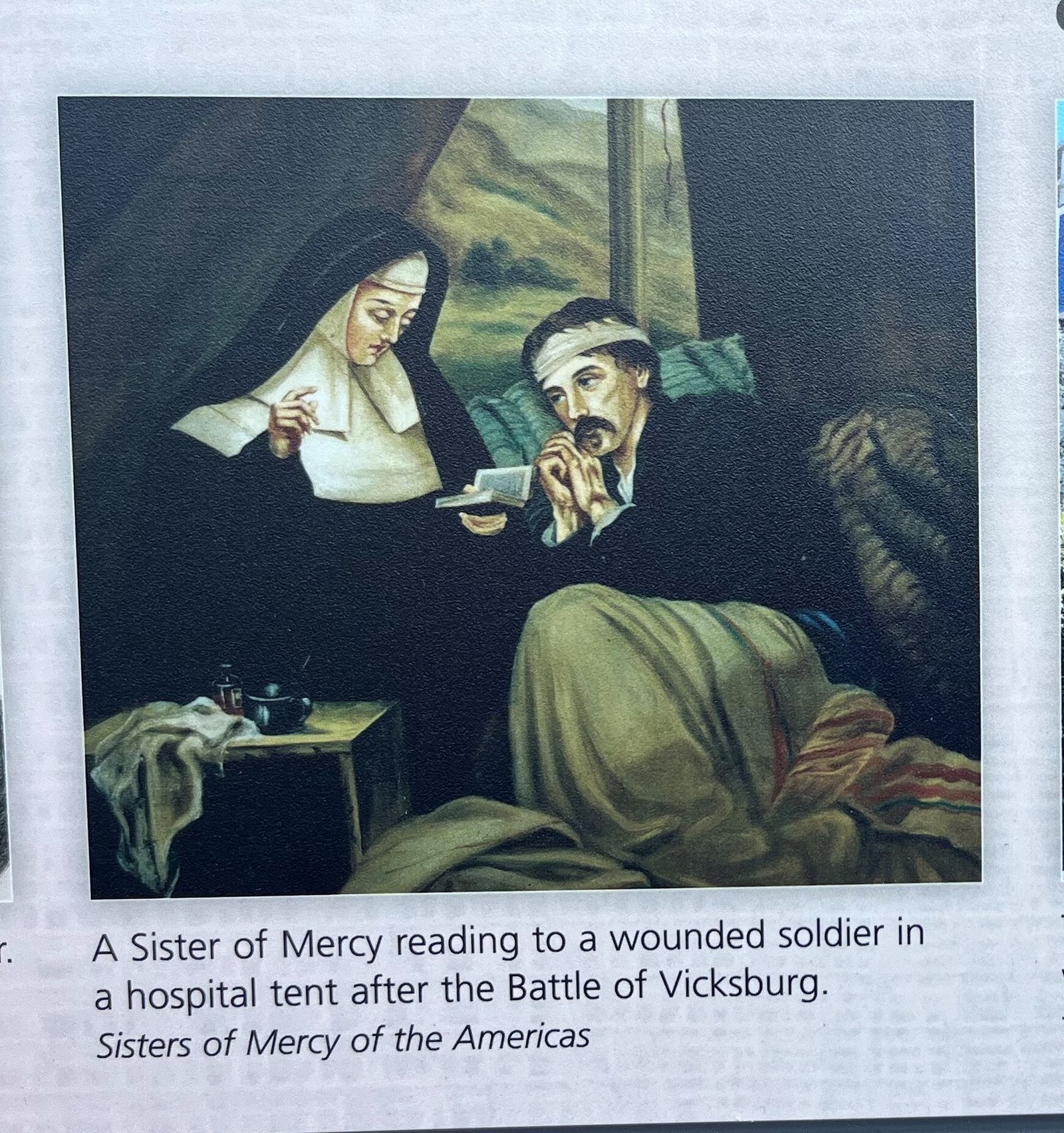

“These wonderful women religious were the hands, voice and face of God to countless wounded soldiers. And during the Civil War, they did not distinguish between Confederate or Union soldiers – they treated each one as would have Christ Himself,” said Cardinal Wilton Gregory, the main celebrant at the Mass at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle.

Cardinal Gregory pointed out that the monument, which stands across the street from the cathedral in downtown Washington, “pays tribute to those courageous and intrepid sisters who did not distinguish between warring parties, but like Jesus served both sides of the conflict with love and compassion.”

In his homily, the cardinal noted that after the Mass, he would be offering a prayer of blessing for the rededication of the monument.

“We thank God for the selfless service of the nuns commemorated in this statue that we honor on the steps of the Cathedral of St. Matthew,” he said, pointing out that day also marked the feast day for the apostle and evangelist St. Matthew, a tax collector who is the patron saint of government workers.

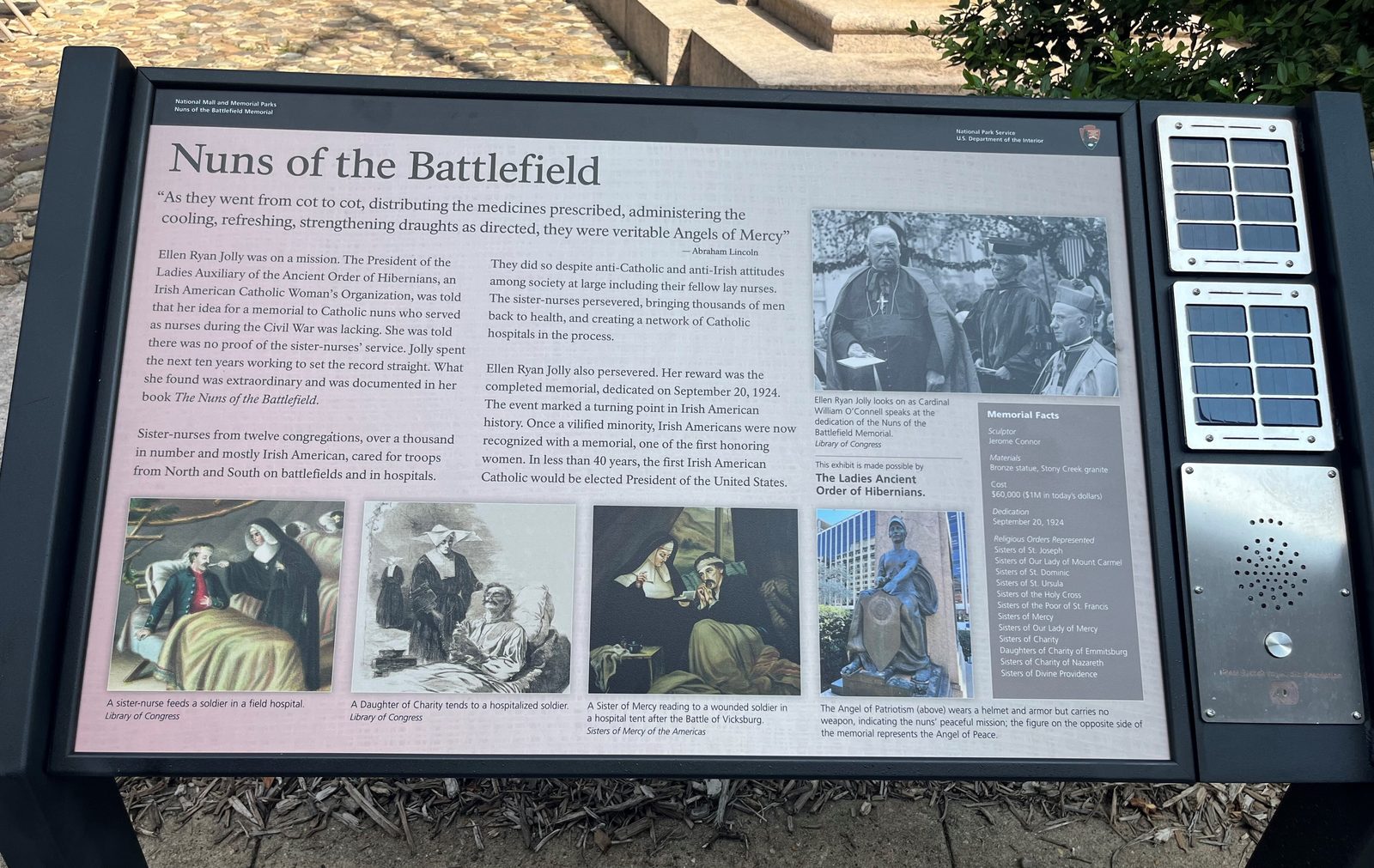

Washington’s archbishop also praised the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians, a national Irish Catholic women’s group, for being the driving force behind the monument honoring those women religious who served as nurses during the Civil War. Members of that group also led an effort to have a wayside marker erected alongside the Nuns of the Battlefield Monument to mark its centennial, and that sign – which includes text, illustrations and an audio component offering background on the monument – was unveiled and blessed that afternoon.

The songs at the Mass reflected the Irish heritage and the patriotism of the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians, with the “Celtic Alleluia” as the gospel acclamation, an “Irish Blessing” as the reflection hymn after Communion, a song to Our Lady of Knock sung as the offertory hymn, and “America the Beautiful” as the closing hymn. The group’s officers served as lectors and brought up the offertory gifts.

Standing on the steps of St. Matthew’s Cathedral after the Mass for the rededication of the Nuns of the Battlefield Monument, Cardinal Gregory faced the nearby monument and in his blessing repeated the words inscribed on the memorial, noting that the women religious who served as nurses on battlefields and in hospitals during the Civil War “comforted the dying, nursed the wounded, carried hope to the imprisoned, gave in his name a drink of water to the thirsty.”

The granite Nuns of the Battlefield Monument near the intersection of Rhode Island Avenue, M Street and Connecticut Avenue in Northwest Washington, D.C., includes a 6-feet tall and 9-feet wide bronze bas relief panel by sculptor Jerome Connor depicting 12 nuns with differing headdresses and habits representing the religious orders whose nuns served as nurses during the Civil War. Flanking the sides of the monument are bronze sculptures representing the Angel of Patriotism and the Angel of Peace.

The religious orders represented on the sculpture include the Sisters of St. Joseph, the Sisters of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the Sisters of St. Dominic, the Sisters of St. Ursula, the Sisters of the Holy Cross, the Sisters of the Poor of St. Francis, the Sisters of Mercy, the Sisters of Our Lady of Mercy, the Sisters of Charity, the Daughters of Charity of Emmitsburg, the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth and the Sisters of Divine Providence.

“They are a group of heroines who risked life and limb to go on the battlefields to treat soldiers who were wounded, and cared for those who were dying… They were selfless,” said Sister Kathleen Szpila, a Sister of St. Joseph of Philadelphia who is an art historian and faculty member at Chestnut Hill College there.

In an interview before the Mass, she noted that the sisters serving as nurses during the Civil War in makeshift hospitals “brought order, cleanliness and food to a chaotic scene.”

Another hero

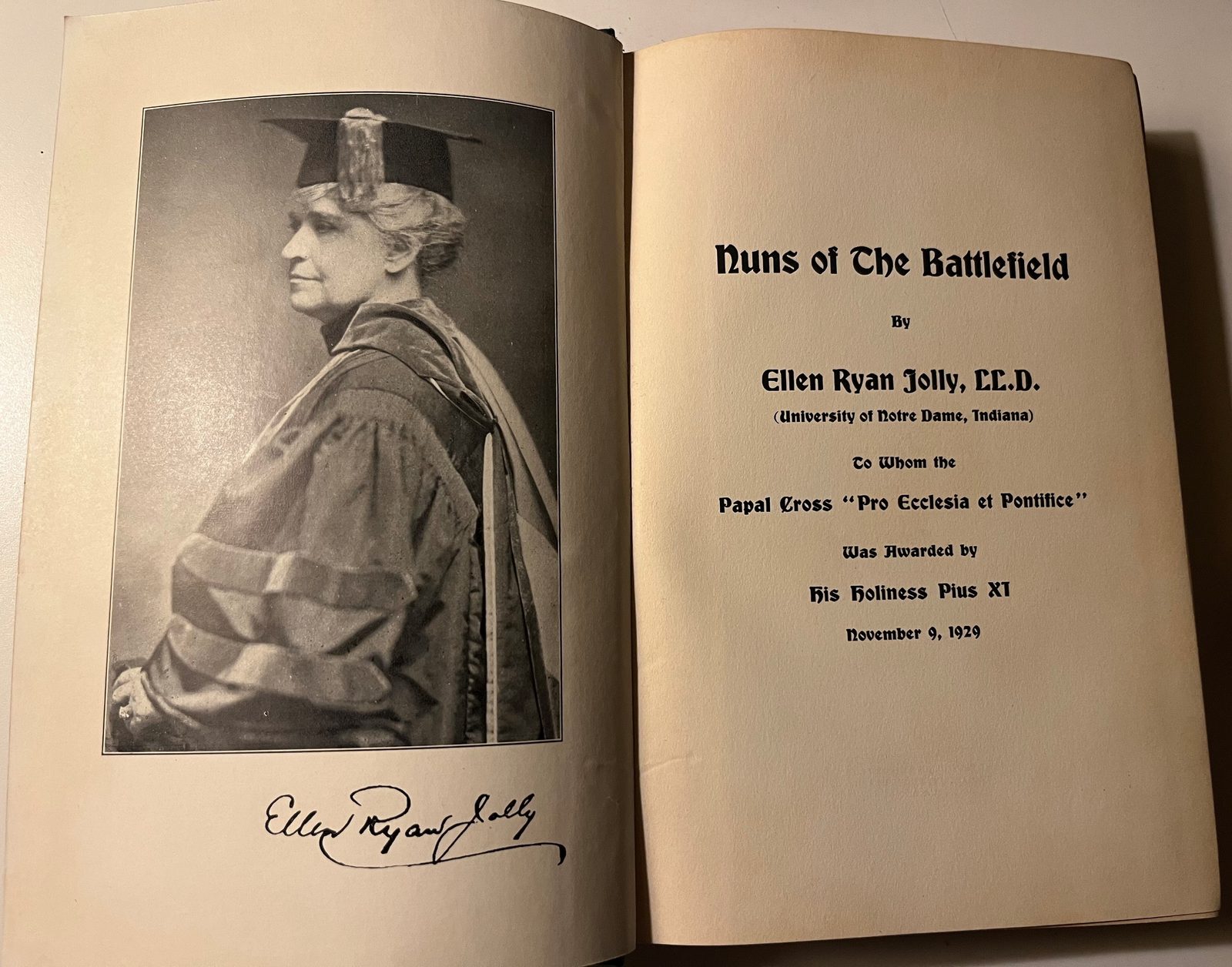

The 100th anniversary commemoration also offered a time to remember another hero, Ellen Ryan Jolly, who as the leader of the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians in 1914 proposed the monument, led the effort to have it made, and after a decade of researching the women religious who served as nurses in the Civil War and advocating for the monument’s completion, she participated in the Sept. 20, 1924 “Sisters’ Day” celebration in Washington, D.C., when thousands of people attended the dedication of the new Nuns of the Battlefield Monument.

Sister Kathleen Szpila wrote a 2012 essay, “Lest We Forget: Ellen Ryan Jolly and the Nuns of the Battlefield Monument” for the American Catholic Studies journal, and after the Mass marking the monument’s centennial and its rededication and a ceremony for the new wayside marker, she spoke at a dinner sponsored by the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians at the Army and Navy Club.

Ellen Ryan Jolly, the daughter of Irish immigrants, was a Rhode Island resident who worked as an elementary school teacher and principal and also had a hat-making business. Sister Kathleen’s article noted that Jolly was proud of her Irish and Catholic heritage and had lasting respect for the women religious who taught her. As the 50th anniversary of the end of the Civil War neared, Jolly knew that many women religious had served as nurses in that war. After proposing that a monument be built to honor them, Jolly was told by the the U.S. War Department that proof was needed before such a memorial could be erected on federal land in the nation’s capital.

So Jolly embarked on a decade-long mission to find that proof, visiting the mother houses of religious congregations across the United States, combing their archives, interviewing surviving sister-nurses, and gathering vivid eyewitness accounts and moving firsthand testimonials. While raising money for the proposed monument, Jolly and other members of the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians also lobbied members of Congress until finally a bill to establish the Nuns of the Battlefield Monument was passed in 1918, and President Woodrow Wilson signed it into law.

In 1924, Jolly unveiled the memorial at its dedication, and three years later, her book, “Nuns of the Battlefield,” was published. The book included 21 chapters offering accounts of the service of women religious as nurses in the Civil War, and each chapter ended with a list that reads like an honor roll of the names of women religious from those orders who served as sister-nurses, and the country or state of their birth. Jolly listed nearly 600 names, and estimated there were hundreds more, perhaps totaling more than 1,000 women religious who were nurses in that war. And she found that more than 90 percent of those sister-nurses were either born in Ireland or were the daughters of Irish immigrants.

In her essay, Sister Kathleen Szpila noted, “The Nuns of the Battlefield Monument stands in Washington, D.C., today because of the vision, the persistence and the dedication of Ellen Ryan Jolly.”

That monument, she wrote, offered a “proclamation in bronze and stone, that even Irish Catholic women, even vowed Catholic sisters, proved their bravery and patriotism as they assisted thousands of wounded and dying soldiers, both Union and Confederate.” That witness challenged the anti-Catholic and anti-Irish prejudices then prevalent in American society. In 2018, Ellen Ryan Jolly became the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate degree from the University of Notre Dame. She died in 1938.

“I think she’s one of the most amazing women I’ve ever come to know,” said Sister Kathleen Szpila of her research subject. “I saw her spirit in the Irish American sisters who taught me. I recognized her determination. Nobody was going to stand in her way.”

Honoring a legacy

Before the Mass and rededication of the Nuns of the Battlefield Monument, Marian O’Donnell Reynolds, a member of the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians from Cleveland who has worked over the years as an ER and ICU nurse, expressed her admiration for those women religious who served as nurses during the Civil War.

“They’re all saints. Look at what they did. They went into battle. It didn’t matter if they (the wounded soldiers) were wearing blue or grey, they took care of them,” she said.

Marilyn Madigan, the immediate past president of the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians, led the effort to establish a wayside marker for the 100th anniversary of the Nuns of the Battlefield Monument, so people walking by could read the sign and understand the memorial’s background.

“It’s personal for me,” said Madigan of her effort to add the wayside marker to the memorial honoring the sister-nurses in the Civil War who were called “angels of mercy.” She worked as a hospital nurse in Cleveland for 41 years, was named after a Sister of St. Joseph, and she researched Irish history for the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians.

Later during a ceremony, Madigan unveiled the new wayside marker along with Jacqueline Jolly, the great-granddaughter of Ellen Ryan Jolly, and the marker was blessed by Bishop Alfred Schlert of Allentown, Pennsylvania, the national chaplain of the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians who was a concelebrant at the anniversary Mass. Maura McSweeney played “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” on the fife, a woodwind instrument that was played during the Civil War. The dignitaries present included Mary Ann Lubinsky, the current national president of the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians. Leaders of that group posed for photos in front of the monument, as did women religious who were in attendance.

Beforehand, Jacqueline Jolly in an interview reflected on her great-grandmothers’ legacy, noting how Ellen Ryan Jolly was proud of her Irish and Catholic heritage and greatly admired the nation’s women religious, and when she came to Washington, “she saw a lot of monuments here are dedicated to generals and soldiers, and she said there are no monuments dedicated to the women who were there helping.”

Expressing her admiration for the women religious who were Civil War nurses, Jacqueline Jolly said, “They just wanted to care for and comfort their fellow man.”

An example that resonates today

Among those speaking at the dedication of the new wayside marker for the Nuns of the Battlefield Monument was Glenn Klaus, a graphic designer for the National Park Service who designed the marker. He noted how many of the sister-nurses had survived famine and oppression in their native Ireland and then lived in the United States during a time of anti-Catholic and anti-Irish prejudice.

“So despite the hostile environment, when the Civil War broke out, sister-nurses flocked to the battlefield to help,” Klaus said. Their mission, he said, “was a call to serve humanity. Thus they treated men from both sides of the conflict. While doing so, they endured the prejudice from their fellow nurses, as well as exposure to the diseases that actually claimed the majority of lives during the Civil War. But they persevered. They brought peace to dying soldiers and aided in the recovery of thousands more. But sadly, their heroic service was largely forgotten shortly after the Civil War.”

“But enter our heroine, Dr. Ellen Ryan Jolly, and the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians. Jolly did not want to see the story of the nuns of the battlefield forgotten, so in 1914, she proposed a Nuns of the Battlefield Memorial,” Klaus said. He noted how military officials asked for proof of the sisters’ service, and Jolly set out on her 10-year mission to document that history.

The text on the wayside marker notes that Ellen Ryan Jolly persevered, just as the sister-nurses who served in the Civil War had persevered. The commentary on the marker states, “Her reward was the completed memorial, dedicated on September 20, 1924. The event marked a turning point in Irish American history. Once a vilified minority, Irish Americans were now recognized with a memorial, one of the first honoring women.”

As he concluded his remarks, Klaus noted that the example of the women religious who served during the Civil War offers a lesson for Americans today.

“We live in divided times, right? So in these times, we can continue to draw meaning from this memorial. The sister-nurses’ examples of caring for others despite their ideology or where they came from still resonates,” Klaus said. He added, “Their determination to do the right thing, despite being surrounded by hate, continues to inspire. And their willingness to help their fellow man, with no promise of a thank-you or compensation, is an example we should all revere.”

In an interview after the ceremony, Sean Pender, the national president of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, said the story of the women religious who served as nurses during the Civil War “is about total sacrifice, doing the right thing, doing God’s work… Their fellow man needed help, and they were there for it.”

And he also expressed admiration for the members of the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians, who led the effort to have the monument established 100 years ago and to have the wayside marker erected for the centennial commemoration. “It doesn’t surprise me. I know the passion and determination of Irish Catholic women,” Pender said.

The guests at the Mass and ceremony included Sister Kathleen Lunsmann, a member of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary who serves as the president of SOAR! (Support Our Aging Religious), a group that raises funds and provides grants to help Catholic religious orders care for aging members. She noted that during the Civil War, women religious were responding to the needs of the time, just as they are doing in many different ministries today.

“Sisters definitely have a role in the making of America,” she said.

Related story:

Some Civil War ‘nuns of the battlefield’ whose orders have historic ties to the Archdiocese of Washington